The first unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone, for use in the fire service was introduced at the 2011 Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) International in Indianapolis. Thousands of drones have been sold to first responder agencies since then. According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), “Public safety agencies’ (PSAs) use of UAVs has grown and will continue to grow.”1 In fact, the FAA notes that by midyear 2020, 2,399 PSAs had an active fleet size of 10,156 based on FAA 14CFR Part 107 registrations and that this fleet size will grow to more than 30,000 by 20252 (the FAA regulation under which pilots fly in PSA drones weighing under 55 pounds; they are referred to as “sUAVs”).

The FAA includes in the category of PSAs the following: law enforcement, firefighting, responses to natural disasters, and emergency medical services. It defines a UAV as consisting of an unmanned aircraft, the control station, and “the associated common links required for safe and efficient operation in the national air system.”3

DRONE BENEFITS

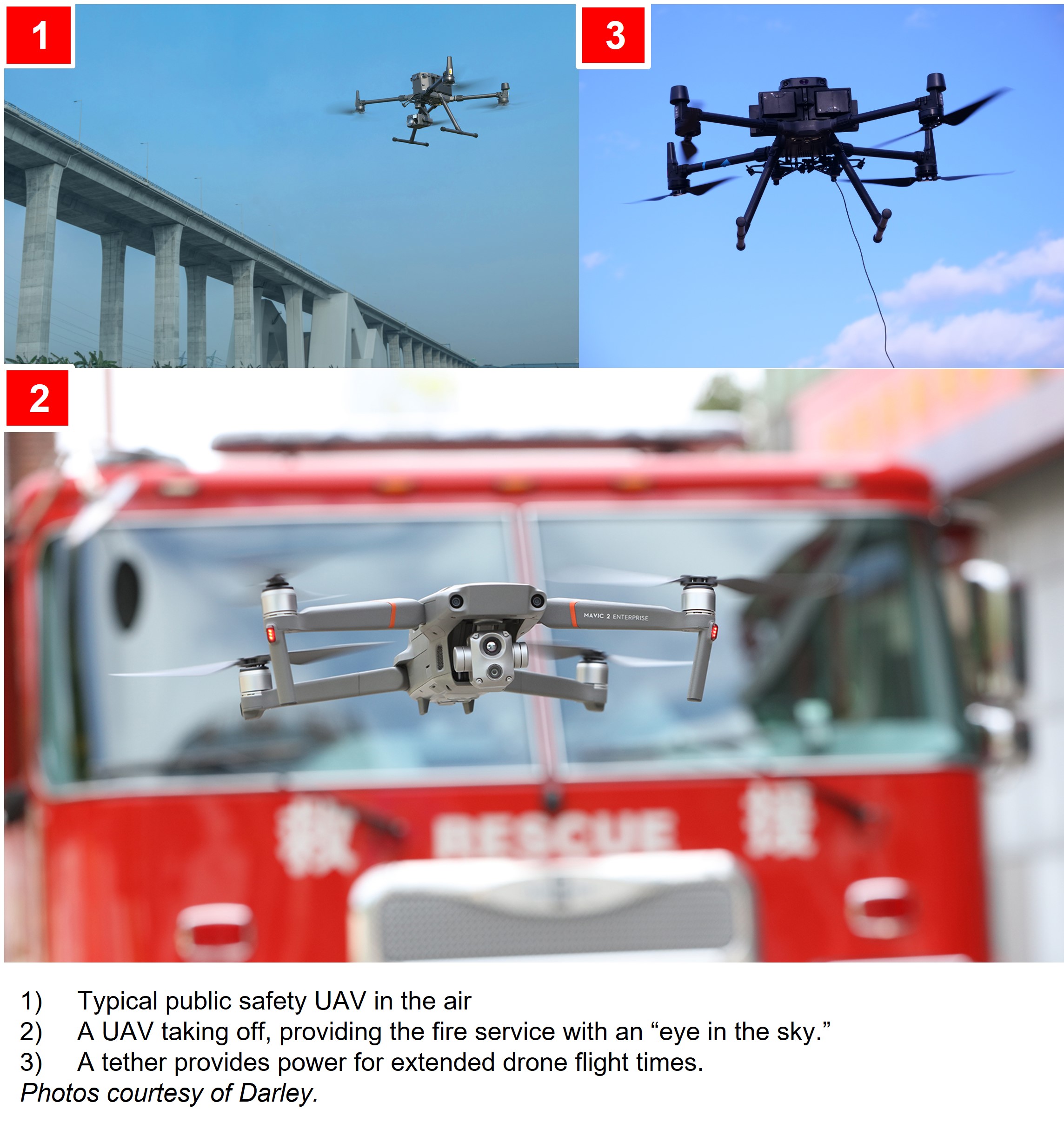

UAVs provide an eye in the sky for first responders. They facilitate first responders’ getting a clear view of the four sides of the fire structure so they can adequately size up the conditions on the fireground; the incident commander can view all four sides from his command vehicle.4 These real-time images from the drones make it possible to devise a plan for mitigating the emergency more quickly, track firefighters on the fireground, detect potential victims in windows or on balconies, and select parking spots for apparatus.5 UAVs have also been found to be effective in hazmat responses, overseeing crowds and traffic, some wildland operations, and search and rescues.

ADVANCEMENTS IN UAVs

Today’s UAVs offer artificial intelligence capabilities that include multidirectional sensing, positioning options, systems for avoiding obstacles, and simplified autonomous capabilities. Other updates include the following:

- Improved battery life.

- Tethering capability for continuous flight time.

- Improved data security features.

- Improved payload capabilities, including the ability to carry multiple cameras, thermal imaging cameras, lighting, and hazmat and chemical-detection devices.

- Modular designs for compact storage.

- Improved drone health and status monitoring.

- Improved rapid deployment packages.

ADDING A DRONE?

If you are thinking about adding a drone component to your department or organization, discuss the need for such a program and its potential uses with your administration. Determine whether the drones should be integrated into or added onto your emergency vehicles.

Cost. A drone for public safety use can cost from $7K up to $100K-plus. Prices vary with the UAV’s capabilities, features, and accessories. Some departments start with an entry-level professional UAV package, which can include a thermal imaging camera and lights.

Shopping. Contact experts, and research the market for the products available. FAMA member companies provide a wide range of drones for use by fire departments, along with training and after-market support, including helping to set up the drone.

Policy and Training. Select the members who will be part of the program, establish standard operating procedures, and initiate training programs that cover the required basic skill sets.

Standards and Regulations. Government agencies (including federal, state, and tribal), law enforcement, and public safety entities have two options for operating drones under 55 pounds. They can fly under 14 CFR part 107, the small UAS rule. Part 107 allows UAS under 55 pounds at or below 400 feet above ground level, for visual line-of-sight operations only. The other option is to fly under the statutory requirements for public aircraft [49 U.S.C. §40102(a) and § 40125] and to operate with a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) to be able to self-certify UAS and operators for flights performing governmental functions.6-7

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 2400, Standard for Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS) Used for Public Safety Operations, 2019 edition, covers the minimum requirements relating to the operation, deployment, and implementation of small, unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS) for public safety operations.8

Community Education. UAVs impact the community-at-large as well as the fire organization. Educating the public about the proposed program and answering any questions that citizens may have will help maintain public trust and alleviate concerns about privacy.

EMERGING TECHNOLOGY

Technological improvements on the horizon for drones used for public safety include the following:

- Larger payload and tether systems and improved lighting and integration technology that will enable drones with high lumen LED lighting to improve nighttime operations.

- Improved intelligence and integration of multiple software programs.

- Improved telemetry data from pilots on scene, as well as advanced Geographic Information System tools.

- Improved 3D mapping and modeling.

As UAV technology advances and applications for these vehicles’ use in firefighting and search-and-rescue expands, more fire departments will look to them as an aspect for increasing efficiency and safety. “UAS technologies offer a tremendous leap forward in capabilities for the fire service,” states the International Association of Fire Chiefs on its web site. The statement continues: “Not only do they give smaller departments the ability to have an aerial program without expensive aircraft, pilots, and the maintenance associated with those assets, but the potential for new strategies and tactics could change operations drastically.”9

FAMA is committed to the manufacture and sale of safe, efficient emergency response vehicles and equipment. FAMA urges fire departments to evaluate the full range of safety features offered by its member companies.

FAMA Forum creative content is contributed by unpaid volunteer authors. Any opinions expressed herein are exclusively those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of FAMA or its member companies.

References

- “FAA Aerospace Forecast Fiscal Years 2021-2041: Unmanned Aircraft Systems [Part 107 unmanned aircraft” https://www.faa.gov/data_research/aviation/aerospace_forecasts/media/Unmanned_Aircraft_Systems.pdf , 44.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 63-64.

- Ibid,44.

- “So, You Want to Buy a Drone,” Matt Sloane, Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment, Nov. 4, 2014.

- “Drones in Public Safety: A Guide to Starting Operations.” https://www.faa.gov.

- Additional information is available in “Operate a Drone, Start a Drone Program” at https://www.faa.gov/uas/public_safety_gov/drone_program/ and at Drones in Public Safety: A Guide to Starting Operations (faa.gov).

- https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-and-standards/detail?code=2400/.

- “Operational Abilities for Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS)”: https://iafc.org/topics-and-tools/resources/resource/uas-tactics